The arcade golden age of the 1980s and 1990s left behind a legacy of iconic games, but many of the original circuit boards that powered these classics are now deteriorating at an alarming rate. As capacitors leak, traces corrode, and custom chips fail, a grassroots movement of engineers, collectors, and preservationists has emerged to salvage these artifacts of gaming history before they're lost forever. This isn't just about nostalgia—it's about preserving the raw, unfiltered creative vision of developers who worked within extreme technical constraints to create magic.

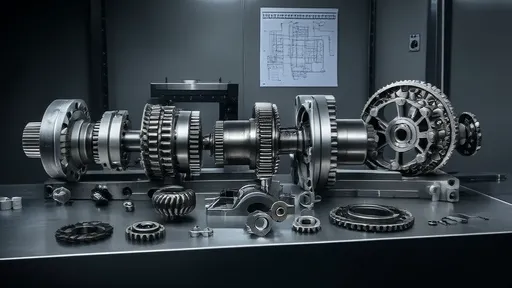

The scale of the problem becomes apparent when examining the fragile nature of arcade hardware. Unlike home consoles designed for durability, arcade boards were commercial products built for short-term profitability. Manufacturers never anticipated these machines would still be operational four decades later. The custom silicon chips (often fabricated using proprietary processes) pose particular challenges—when a Capcom CPS-2 security ASIC fails or a Neo Geo memory controller dies, there are no off-the-shelf replacements. Preservationists have resorted to methods ranging from painstaking chip decapping to FPGA recreations, often working from incomplete documentation.

One breakthrough came when hobbyists discovered that many "dead" boards merely suffered from failed battery backups. The suicide batteries in systems like Sega's Model 2 and Namco's System 11 were designed to erase critical encryption keys when power was cut, rendering the hardware useless. Through reverse engineering, teams developed methods to either replace these batteries before failure or reprogram the security chips entirely. This saved thousands of boards from becoming expensive paperweights, though the work requires microsoldering skills beyond most collectors' abilities.

The community's most ambitious project involves creating comprehensive schematics for obscure boards. While famous systems like the Neo Geo have been well-documented, many regional or low-production PCBs exist only as physical objects. Groups have developed specialized imaging rigs to scan both sides of populated boards simultaneously, then use software to trace connections through multiple layers of scans. The resulting schematics allow for accurate repairs and even full recreations when original boards become too damaged. This process recently brought several rare Japanese mahjong games back from extinction when their proprietary graphic chips failed.

Legal gray areas abound in this preservation work. While most publishers turn a blind eye to firmware dumping for preservation, some actively oppose board cloning efforts—even when they have no commercial interest in the original titles. This has led to an underground network of trusted technicians who share repair knowledge and rare ROM dumps through private channels. The ethical dilemma persists: does a corporation retain moral rights over abandoned hardware they no longer support? Preservationists argue these boards represent cultural heritage beyond corporate ownership.

Perhaps the most heartening development is how this technical salvage operation has fostered international collaboration. When a rare European arcade variant of a game surfaces with unique bugs, programmers in Japan and hardware experts in America will often work together to diagnose the issue. Online forums have become living museums where repair logs read like forensic investigations, with contributors comparing corrosion patterns or debating the merits of different flux compounds. This global brain trust has developed innovative techniques, like using ultrasonic cleaners to revive boards damaged by soda spills or cigarette smoke residue.

The work extends beyond mere functionality. Original arcade boards often contained quirks and bugs that defined gameplay—the slightly uneven collision detection in a fighting game or the unique slowdown patterns in a shoot-em-up. Emulators frequently "correct" these imperfections, altering the authentic experience. Preservationists now document these behaviors as intentional features, arguing that a perfect port loses something essential. Several recent museum exhibitions have gone to great lengths to display games on original, repaired hardware rather than emulation setups.

Looking forward, the community faces new challenges as surface-mount technology replaces the through-hole components of classic boards. Modern arcade systems use BGA chips and multilayer PCBs that are nearly impossible to repair without industrial equipment. Some worry this marks the end of an era where dedicated individuals could keep these systems alive. Yet the same was said about repairing 1980s vector displays until recent breakthroughs in recreating their analog components. If history is any guide, where there's passion for preservation, ingenious solutions will follow—even if it means building custom microscopes or developing new PCB trace repair techniques along the way.

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025