The field of DNA data storage has reached an inflection point where researchers are no longer asking if biological molecules can serve as viable archival media, but rather how quickly and at what scale we can implement this revolutionary technology. At the heart of this transition lies the critical challenge of write parallelization - the ability to simultaneously encode digital information across multiple DNA strands without compromising data integrity or synthesis accuracy.

Breaking the Serial Bottleneck

Traditional DNA synthesis methods have followed a fundamentally serial approach, building oligonucleotides one nucleotide at a time in sequential chemical reactions. This molecular assembly line, while reliable for research applications, becomes prohibitively slow when attempting to write even modest datasets. A single megabyte of data encoded in DNA requires the synthesis of millions of unique oligonucleotides - a task that could take months using conventional techniques.

Recent breakthroughs in parallel synthesis technologies are shattering this bottleneck. Companies like Molecular Assemblies and DNA Script have developed enzymatic synthesis platforms that can simultaneously grow thousands of distinct DNA strands. Unlike phosphoramidite chemistry which builds strands sequentially, these enzymatic methods leverage nature's own replication machinery to add bases in parallel across multiple growing strands.

The Spatial Parallelization Revolution

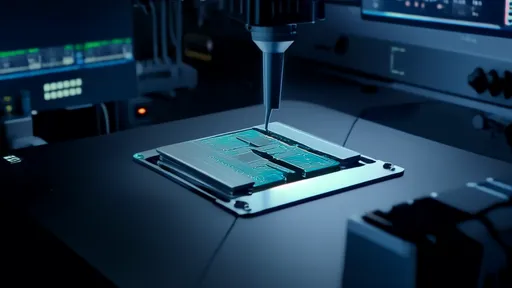

Perhaps the most promising approach comes from spatial addressing techniques adapted from semiconductor manufacturing. Researchers at the University of Washington and Microsoft Research have demonstrated DNA synthesis on silicon chips containing thousands of microscopic wells. Each well functions as an independent reaction chamber where unique DNA sequences can be synthesized simultaneously. This method, reminiscent of how computer chips contain billions of transistors operating in parallel, could theoretically scale to millions of parallel synthesis sites.

What makes spatial addressing particularly powerful is its compatibility with existing photolithography equipment. By repurposing tools developed for computer chip fabrication, scientists can leverage decades of semiconductor industry advancements in miniaturization and parallel processing. Early prototypes have shown the ability to write hundreds of thousands of unique DNA sequences in a single run, with synthesis densities approaching 10 million features per square centimeter.

Error Correction in Parallel Systems

As with any parallel system, error rates become magnified with scale. Traditional DNA synthesis might produce error rates around 1 in 100 bases, which becomes unacceptable when writing billions of bases simultaneously. New error correction methods are proving critical to making parallel DNA writing viable.

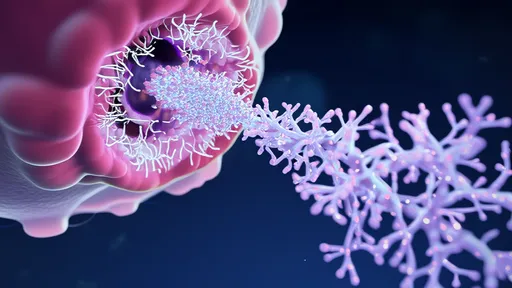

Forward error correction schemes adapted from telecommunications are being implemented at the molecular level. By encoding redundant information across multiple strands and using consensus algorithms during sequencing, researchers can achieve effective error rates below 1 in 10,000 - approaching what's needed for commercial data storage applications. Some teams are even incorporating error-detecting nucleotides directly into the synthesis process, allowing for real-time quality control during parallel writing.

Molecular Addressing and Random Access

True parallelization requires more than just simultaneous synthesis - it demands the ability to selectively access specific data segments within vast molecular libraries. Recent work in PCR-based addressing has shown promise, using unique primer binding sites as molecular "address lines" that can selectively amplify desired data blocks from a complex mixture.

More innovative approaches are borrowing concepts from computer memory architecture. Researchers at ETH Zurich have demonstrated a hierarchical addressing system where DNA strands contain both local addresses (similar to RAM addresses) and broader block identifiers (akin to memory banks). This two-tier system allows for efficient random access while maintaining high storage densities.

The Role of Machine Learning

Optimizing parallel DNA writing presents a multidimensional challenge that's perfectly suited for machine learning approaches. Neural networks are being employed to predict optimal encoding schemes, minimize synthesis errors, and even design DNA sequences that resist degradation during storage.

At Stanford's Bioengineering Department, researchers have developed reinforcement learning systems that continuously improve synthesis conditions based on real-time feedback from millions of parallel reactions. These AI "controllers" can adjust temperature, pH, and reagent concentrations across different regions of synthesis chips to maximize yield and accuracy.

Scaling Challenges and Economic Realities

While the technical achievements are impressive, significant hurdles remain before parallel DNA writing reaches commercial viability. The current cost per megabyte stored in DNA remains orders of magnitude higher than magnetic or optical storage, though the cost curve is following a steep downward trajectory similar to DNA sequencing costs a decade ago.

Perhaps the most pressing challenge is developing a complete ecosystem around DNA data storage. Parallel writing is just one component - we equally need advances in parallel reading, long-term preservation, and standardized encoding formats. Industry consortia are beginning to form around these challenges, with organizations like the DNA Data Storage Alliance working to establish technical standards and use cases.

Biological vs. Synthetic Approaches

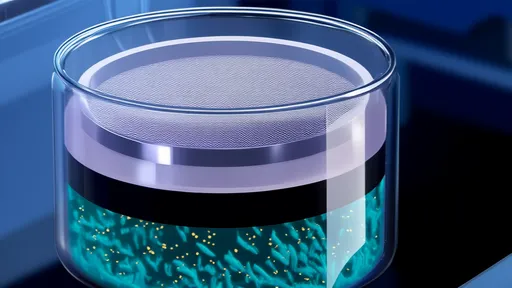

An interesting philosophical divide has emerged in the field between purely synthetic approaches and those that leverage biological systems. Some researchers argue that the most scalable path forward involves engineering living cells to act as parallel DNA writers, essentially programming bacteria to encode data through their natural replication processes.

Others maintain that completely synthetic, cell-free systems offer better control and avoid the complications of biological variability. Recent hybrid approaches suggest there may be a middle ground - using purified biological enzymes in controlled synthetic environments to get the best of both worlds.

The Road Ahead

As parallel writing techniques mature, we're beginning to see the first glimmers of practical DNA storage systems. Earlier this year, a collaboration between Twist Bioscience and Microsoft successfully stored and retrieved over 1GB of data in DNA - small by conventional storage standards, but a watershed moment for molecular data storage.

The coming years will likely see exponential growth in both capacity and speed as parallelization techniques improve. Some projections suggest we could see petabyte-scale DNA archives within a decade, with write speeds approaching those of early hard drives. While DNA may never replace flash storage for everyday computing, its potential as an ultra-dense, long-term archival medium is becoming increasingly undeniable.

What makes this technological trajectory particularly exciting is how it represents a true convergence of biology and information technology. The tools of computer science are being applied to biological systems, while biological principles are inspiring new computing architectures. In this interdisciplinary space, DNA data storage stands as one of the most tangible examples of how these fields can transform each other.

The parallelization of DNA writing isn't just an engineering challenge - it's a fundamental rethinking of how we approach information storage at the most basic level. As we learn to harness the innate parallelism of molecular systems, we may be witnessing the birth of an entirely new paradigm in data storage, one that could preserve humanity's knowledge for millennia to come.

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025