The quest for sustainable energy solutions has led scientists to explore unconventional avenues, one of which is the microbial fuel cell (MFC). These fascinating devices harness the metabolic activity of microorganisms to generate electricity, offering a glimpse into a future where wastewater treatment plants could double as power stations. While the concept is elegant in its simplicity, the efficiency of MFCs remains a critical hurdle preventing widespread adoption.

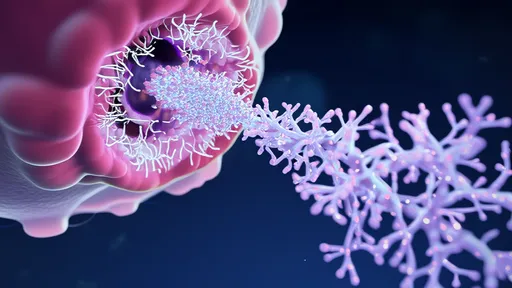

At the heart of every MFC lies a delicate dance between bacteria and electrodes. Certain species of electroactive bacteria, such as Geobacter and Shewanella, possess the remarkable ability to transfer electrons extracellularly during their metabolic processes. When these microbes break down organic matter in the anode chamber, they release electrons that travel through an external circuit to the cathode, creating an electric current. The efficiency of this energy conversion process depends on numerous interconnected factors that researchers are still working to optimize.

One of the most significant challenges in MFC technology stems from the inherent limitations of bacterial metabolism. Even under ideal conditions, microbes cannot convert all the chemical energy in their substrate into electrical energy. A substantial portion gets lost as heat or gets diverted toward bacterial growth and maintenance. The theoretical maximum efficiency of MFCs, based on thermodynamic principles, rarely exceeds 50%, and practical systems typically achieve far less. Recent studies suggest that cutting-edge MFC designs are reaching conversion efficiencies around 30-40%, though these numbers vary dramatically depending on the specific configuration and operating conditions.

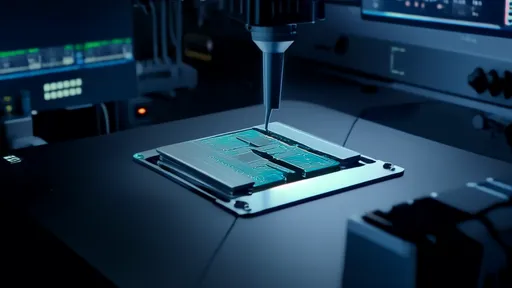

Electrode design has emerged as a crucial factor influencing MFC performance. Traditional carbon-based electrodes, while cost-effective, often fail to provide the optimal surface area and conductivity needed for efficient electron transfer. Researchers are experimenting with novel materials like graphene-coated electrodes and three-dimensional nanostructures that dramatically increase the available surface area for bacterial colonization. These advanced materials not only improve electron transfer rates but also enhance the overall power density of the system. However, the trade-off between performance gains and material costs remains a significant consideration for practical applications.

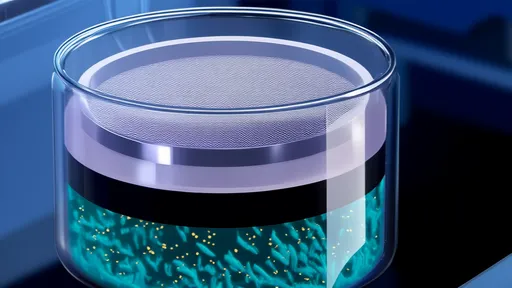

The choice of proton exchange membrane (PEM) represents another critical efficiency determinant in MFC design. This component separates the anode and cathode chambers while allowing protons to pass through, completing the electrical circuit. Conventional PEMs, borrowed from chemical fuel cell technology, often prove too expensive or inefficient for microbial systems. Bioengineers are developing alternative membranes using cheaper materials like ceramics or even biological polymers that show promise in reducing internal resistance while maintaining proper ion selectivity.

Operational parameters exert tremendous influence on MFC efficiency. Factors such as pH balance, temperature, substrate concentration, and hydraulic retention time must be carefully controlled to maintain optimal microbial activity. Many studies demonstrate that moderate thermophilic conditions (around 40-50°C) can enhance reaction kinetics and improve overall system performance. Similarly, maintaining the right balance of organic loading is crucial—too little substrate starves the bacteria, while too much can lead to clogging or the growth of inefficient fermentative microbes that don't contribute to electricity generation.

Scaling up MFC systems introduces additional efficiency challenges that aren't apparent in laboratory settings. While small-scale reactors might show promising results, increasing their size often leads to disproportionate losses in performance. This scaling effect stems from increased internal resistance, uneven substrate distribution, and difficulties in maintaining uniform conditions throughout larger volumes. Some innovative approaches to this problem involve designing modular systems where multiple smaller MFC units operate in parallel rather than attempting to build single, massive reactors.

The microbial community composition plays an underappreciated yet vital role in determining MFC efficiency. Pure cultures of known electrogenic bacteria often underperform compared to carefully selected mixed communities. In these complex ecosystems, different species perform complementary functions—some excel at breaking down complex organics, while others specialize in electron transfer. Maintaining the right balance within these microbial consortia requires careful system management, as shifts in population dynamics can dramatically affect power output. Recent metagenomic studies are helping researchers understand these interactions at a fundamental level, potentially leading to better community engineering strategies.

One promising avenue for improving MFC efficiency lies in genetic engineering of the microbes themselves. By modifying bacterial genomes to enhance their electron transfer capabilities or redirect metabolic pathways toward more efficient energy extraction, scientists hope to create "superbug" strains optimized for electricity generation. While this approach raises certain ethical and ecological concerns, the potential efficiency gains could make MFCs competitive with conventional energy sources for specific applications.

The integration of MFCs with other treatment processes presents interesting opportunities for overall system efficiency. Some researchers are exploring hybrid systems where microbial electrolysis cells or phototrophic organisms complement traditional MFCs. These combinations can sometimes extract more useful energy from the same organic input while accomplishing additional treatment objectives. For instance, coupling MFCs with algae cultivation can simultaneously generate electricity, produce biomass for biofuels, and remove nutrients from wastewater.

Economic analyses suggest that current MFC technologies still struggle to compete with conventional energy sources on pure cost terms. However, when considering their additional benefits—such as wastewater treatment capability, lower carbon footprint, and potential resource recovery—the overall value proposition becomes more compelling. As research continues to push the boundaries of MFC efficiency, these systems may find niche applications where their unique advantages outweigh their current limitations, perhaps in remote locations or specialized industrial settings where conventional power is unavailable or prohibitively expensive.

Looking toward the future, the path to improved MFC efficiency will likely require a combination of materials science, microbial ecology, and process engineering breakthroughs. While significant challenges remain, the potential environmental benefits and the elegant biological principles underlying this technology continue to drive research forward. As our understanding of the complex interactions between microbes and electrodes deepens, we may soon see microbial fuel cells transition from laboratory curiosities to practical components of our renewable energy infrastructure.

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025