The human sense of taste represents one of nature's most sophisticated chemical detection systems, capable of distinguishing subtle molecular differences with remarkable efficiency. Recent advances in neuromorphic engineering have begun unraveling the complex neural coding principles behind gustatory perception, opening new frontiers in artificial intelligence and human-machine interfaces.

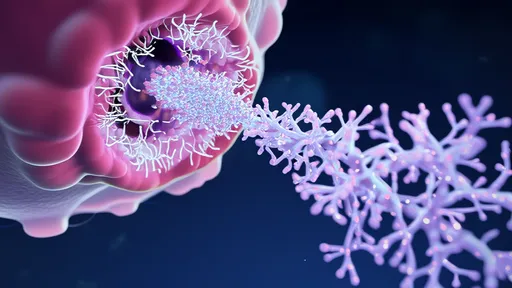

At the heart of this exploration lies the fundamental question: how does the brain transform chemical stimuli into meaningful taste experiences? Traditional models viewed taste as a simple labeled-line system where specific receptors correspond to basic tastes like sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami. However, emerging research reveals a far more dynamic and distributed neural representation that challenges these classical notions.

The neuromorphic approach to understanding taste coding draws inspiration from the brain's actual biological circuitry rather than abstract computational models. Scientists are discovering that taste information undergoes extensive processing across multiple hierarchical levels - from receptor cells in taste buds to neural circuits in the brainstem, thalamus, and ultimately the insular cortex. Each stage performs sophisticated transformations that current electronic systems struggle to replicate.

One groundbreaking discovery involves the population coding mechanism in gustatory circuits. Unlike digital systems that rely on precise individual neuron firing, taste information appears encoded in distributed patterns across neuron ensembles. This explains our ability to recognize flavors even when some sensory input is degraded - a robustness that artificial systems desperately need.

Temporal dynamics play an equally crucial role in taste encoding that most artificial systems overlook. The timing between neural spikes carries substantial information beyond simple firing rates. Certain taste qualities appear to be represented by distinct temporal patterns that evolve over hundreds of milliseconds, creating what researchers call a "taste fingerprint" in neural activity.

Perhaps most fascinating is how neuromorphic studies reveal taste perception to be highly context-dependent. The same chemical stimulus can produce different neural representations based on physiological state (like hunger), previous experience, or even concurrent smells. This explains why food tastes different when we're sick or why childhood flavors evoke powerful memories.

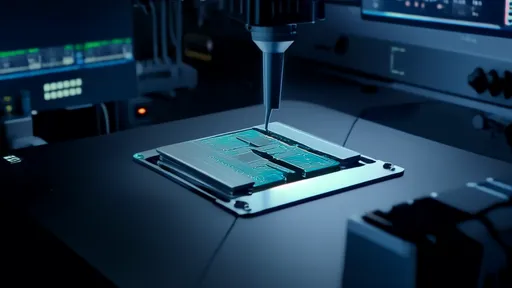

The implications for artificial intelligence are profound. Current electronic tongues and taste sensors pale in comparison to biological systems, typically limited to identifying basic taste categories through straightforward chemical analysis. Neuromorphic engineers are now developing chips that mimic the brain's taste processing architecture, incorporating spiking neural networks and adaptive learning mechanisms.

Several research groups have created silicon gustatory neurons that replicate the biophysical properties of real taste cells. These artificial neurons demonstrate similar response patterns to sweet, bitter, and umami stimuli, including the characteristic phasic-tonic firing patterns observed biologically. When connected in neuromorphic circuits, they begin to exhibit some of the same sophisticated filtering and pattern recognition capabilities as biological taste systems.

Machine learning applications stand to benefit tremendously from these insights. By implementing neuromorphic taste coding principles, AI systems could achieve human-like performance in food quality assessment, pharmaceutical testing, and environmental monitoring. A beverage company could create an AI taster that not only detects chemical composition but actually predicts human flavor perception with unprecedented accuracy.

The medical field presents another promising application area. Neuromorphic taste interfaces could restore gustatory function for patients with damage to taste pathways or help regulate appetite in metabolic disorders. Early experiments show that electrical stimulation of taste cortex areas using biologically-patterned signals can evoke realistic taste sensations.

However, significant challenges remain before we can fully replicate biological taste encoding. The peripheral taste system alone contains at least five distinct receptor cell types with complex interactions. Central processing involves intricate feedback loops with olfactory, somatosensory, and reward systems that current neuromorphic hardware cannot yet accommodate.

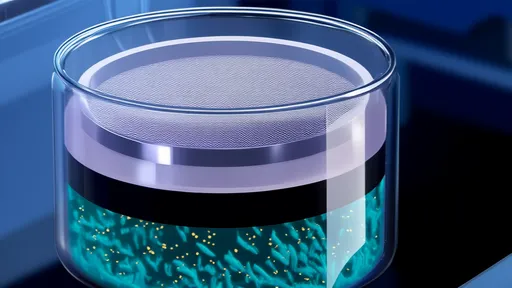

Another hurdle involves the molecular specificity of taste receptors. While we've made progress understanding the neural representation, the front-end chemistry-to-neural signal transduction remains difficult to emulate artificially. Some researchers are exploring hybrid systems that combine biological taste receptors with artificial neural processing.

Ethical considerations also emerge as these technologies advance. The ability to artificially create or manipulate taste experiences raises questions about potential misuse in food marketing or military applications. There's also the philosophical question of whether artificial systems could ever truly "experience" taste or merely simulate its neural correlates.

Looking ahead, the field is moving toward more comprehensive neuromorphic models that incorporate the full gustatory-neural-behavioral loop. This means not just encoding taste signals but also modeling how these signals drive learning, preference formation, and consummatory behaviors. Such complete models could revolutionize everything from nutrition science to addiction treatment.

As research progresses, we're gaining not just better artificial taste systems, but deeper understanding of human perception itself. The neuromorphic approach has revealed taste to be not a passive detection system, but an active, adaptive process tightly integrated with our cognitive and emotional states. This realization may ultimately lead to redefining what we consider "taste" to be at the most fundamental level.

The convergence of neuroscience, materials science, and artificial intelligence continues to accelerate breakthroughs in neuromorphic taste encoding. Within the next decade, we may see commercial applications ranging from hyper-realistic food simulations to personalized nutrition systems that adapt to individual taste preferences at the neural level. One thing is certain - as we decode the brain's taste algorithms, we're not just building better machines, but uncovering the very essence of what makes food meaningful to human experience.

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025

By /Aug 15, 2025